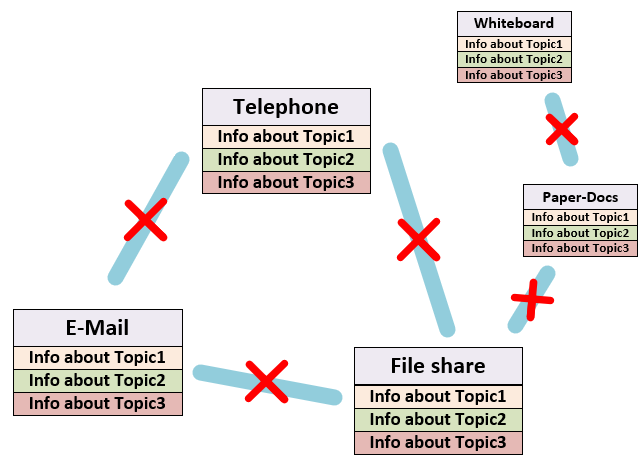

Over the past few decades, three tools had established themselves as leaders in enterprise collaboration:

- Telephone

- E-Mailpostbox

- File share (or DMS)

But since the pandemic at the latest, more and more companies are finding it difficult to make sufficient use of these tools. And this has a simple reason:

There is no techology that connects all three tools.

For example, if you write an e-mail to a colleague about a certain customer project and then work with him on a file, an organizational problem arises:

- Your e-mail and the file are logically related, because they are about the same subject.

- Technically, however, there is no association between the email and the document. Both exist in two separate worlds.

So, at some point, you will find scattered information on all sorts of topics in the “e-mail”, “network drive” and “telephone” pots. Their context is only stored in the heads of the employees:

It gets even worse when you use not only these three tools, but also other things, such as a whiteboard or paper documents.

Fortunately, there are now modern approaches to getting to grips with this problem. These include Google Workspace, iWork and Microsoft 365.

In this article, we would like to go into Microsoft 365 groups in a little more detail, although the principles presented on this page naturally also apply to comparable products.*

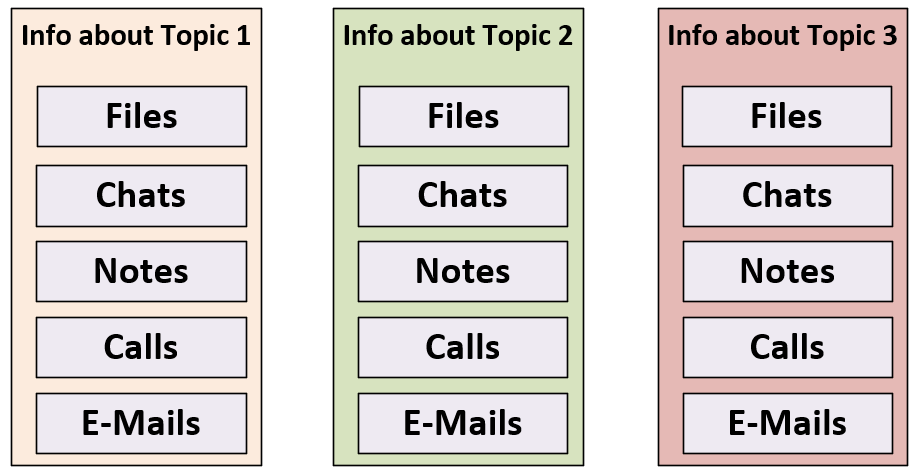

In such groups, various collaboration resources are associated with each other. So you can think of a group as the glue that binds your conversations, emails, documents, notes, etc. together on a particular topic:

This article provides an introduction to the topic.

* That also applies for the here described 4-step-strategy.

The Microsoft 365 Group

A Microsoft 365 Group (formerly also called Office365 Group, Unified Group or Office Group) is a collaboration room.

This room is assigned to a topic, which is defined by the name when the group is created.

Once the group has been created, you will be provided with different areas for this topic to help you in your collaboration.

These areas are for example:

- A Microsoft Team (for conversations)

- A SharePoint Teamsite (for files)

- A common E-Mail Postbox

- A common calendar

- One or more project management plans

- A common notebook

- …

But these are only the most important examples. For a complete presentation, you can read the official documentation here.

But let’s start with an example, because the topic can be a bit confusing at the beginning.

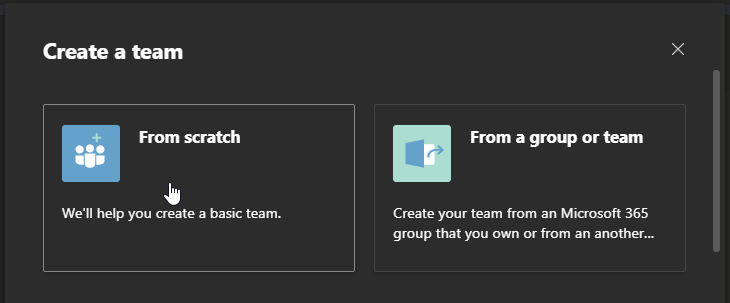

Let’s say you create a new team via the Teams client:

In this example you will create a new empty team without template (from scratch).

Then you have to decide whether your team should be public or private (more about permissions later) and what name the team should have.

If you now confirm, the team appears in the list and you can start creating channels and adding members (more on that later, too).

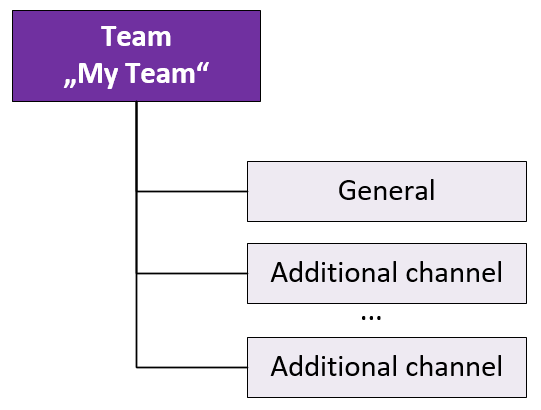

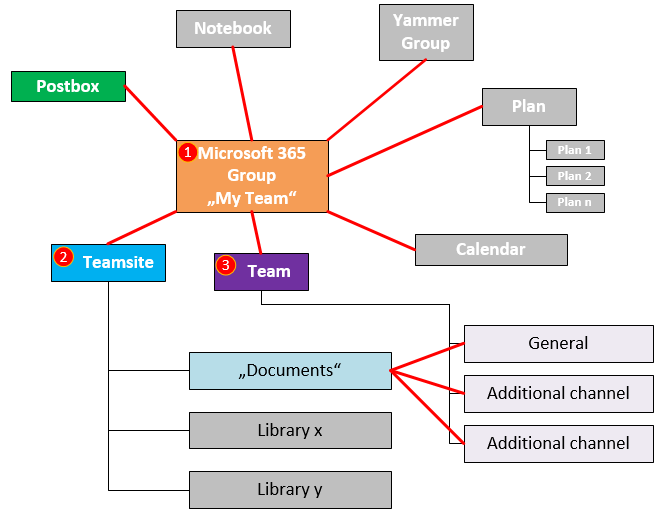

The created structure could be sketched as follows:

Simple, right?

Unfortunately not, because the truth is that there’s a lot more going on in the background than you might initially expect.

Let’s take a quick look at a more accurate picture:

Surprised?

You can see that your action “Create new team” has triggered a whole chain of operations.

In a somewhat simplified way, the following things happen after you click on “Create”:

- A Microsoft 365 group with the name “My Team” is created in the background.

- A team is created for the group, which inherits the name of the group “My Team” and all permissions.

- A SharePoint team page is created for the group, which also inherits the name “My Team” and all permissions.

There are also some gray areas in the image. These show which components could potentially be added to your group.

These are:

- Additional channels (private or public)

- Additional SharePoint document libraries (with certain permissions)

- Any other resources, as already mentioned above.

The whole is more than the sum of its parts

At first glance, this structure may seem a bit cluttered to you.

Why is it necessary to store documents in SharePoint? Couldn’t Teams just manage the documents itself? And why all these other apps? Couldn’t it be simpler?

The answer is quite clearly: No!

Because the goal of Teams was never to create something completely new, but simply to put the tools that were already there into a common context.

These tools were previously independent of each other and could only play to their strengths separately. But now it is possible to use all these tools in a common space. Directly integrated into each other.

The first step towards this goal was the introduction of Microsoft 365 Groups. And a few years later came Teams as the “front door” to the modern workplace.

In the past, there was SharePoint for documents, Skype for Business for telephony, Outlook for mailboxes, and so on.

But in Microsoft Teams, all these powerful tools converge into one.

This means that with Teams you have the full power of SharePoint on your side and this alone offers an incredible amount of potential.

In addition, any number of apps can be integrated into Teams that were not developed by Microsoft itself at all.

So the above structure may be a bit hard to grasp, but it offers almost infinite potential in return.

And fortunately, this structure is also hidden from your users, so only IT needs to understand what’s going on behind the scenes.

The biggest weakness of Microsoft Teams

As is so often the case in the world, the greatest strength of something is also its greatest weakness.

Because an infinite number of possibilities can leave an IT department in a state of shock and raise many questions:

- How do I maintain control over teams? Isn’t there a risk that important information or documents will get lost in the endless flood of channels and their integrated apps?

- How do I train my users properly?

- How do I keep a structure so that chaos doesn’t arise?

- How do I deal with files when the simple authorization structure of teams is not sufficient?

GroupHive was created to find solutions to such questions.

Further basic articles: